Now I can read! (Why didn’t you tell me words make sense?)

By: Jeffrey Bowers | Javiera Morales, Instagram: donde.la.javi; Facebook: Donde la Javi

Hope you enjoy the book! What I want to emphasize here is that our story is not only about Jeff learning to read, but also an introduction to a new form of reading instruction called Structured Word Inquiry (or SWI). SWI is an alternative to phonics and whole language that are, by far, the most common approaches to reading instruction in schools. Here I outline some of the problems with these standard forms of instruction and show why SWI is a promising way forward. My hope is that you are sufficiently intrigued by the illustrations of SWI in our book you will read this essay and explore some of the links below.

Jump to the final sections if you just want a brief introduction into how the English writing system works and SWI. But the story of how we are stuck with phonics and whole language is interesting, full of politics and controversy.

Below you can find links to additional information, including links to published peer-reviewed journal articles and blogposts, a debate between myself and phonics expert Dr. Kathryn Garforth regarding the evidence for phonics, and a conversation between a skeptical teacher Nate Joseph and my brother Peter Bowers where Pete describes SWI in some detail and illustrates how SWI can be taught from the start. There are also links to videos where you can see SWI in action in the classroom.

A brief background on the “reading wars”

Anyone remotely familiar with reading instruction will know that there has been a longstanding and acrimonious debate regarding how children should be taught to read, the so-called “reading wars”. The controversy concerns whether initial instruction should focus on letter-to-sound correspondences so that children learn to sound out words (phonics) or focus on the meanings of written words embedded in meaningful and engaging stories (whole language). What might not be so apparent to an outsider, however, is that there is now near universal consensus in the research community that phonics is the more effective approach. At this point, the controversy is largely between teachers who worry that the joy of reading is lost with phonics, and the research community who argue that many children continue to read poorly because schools are ignoring the science of reading that strongly supports phonics.

Who should a parent trust? The truth is that both camps are fundamentally misguided. The reading wars is a big distraction that has made it difficult for researchers and teachers to objectively look at the evidence and consider alternative approaches. After explaining why neither approach is supported by data or theory, I make the following modest proposal: reading instruction should be designed around the logic of the writing system (something akin to the way that Jeff was taught in our story).

What is the evidence (or lack of evidence) for phonics and whole language?

Most researchers studying reading instruction think it is absurd to claim there is little or no evidence for phonics. Indeed, anyone who dares to question the evidence for phonics is in danger of being derided as naïve or anti-science — akin to questioning the evidence that humans are contributing to global warming or that vaccines are effective. This widespread scientific consensus has been effective in motivating policy change. It led to the legal requirement that all state schools in England teach phonics since 2007, there is a growing pressure to do the same in Australia and USA. Indeed, phonics has just recently become legally required in the state of North Carolina: https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/can-teaching-be-improved-law

But the claim that phonics is more effective than whole language is best explained by politics, ideology, and the sociology of science, not data. As you might imagine, this is a controversial claim amongst researchers, and I appreciate it will be hard from many readers to follow the intricacies of the research, or indeed, want to read the science. Parents just want their children to be taught the best way, and quite reasonably, expect experts to give the best advice based on an accurate characterization of the science. But at the end of the day, science is carried out by people, and sometimes the process goes wrong.

In 2020 I published an article in the journal Educational Psychology Review that reviewed all the evidence at that time. Over many decades there have been well over 100 published studies assessing the effectiveness of phonics, and the results have been summarized in a number of meta-analyses that combine the results of all the relevant studies. Because meta-analyses summarize the results of many studies the results are thought to be more reliable than any given study. The most famous is the National Reading Panel meta-analysis carried out in 2000 that summarized the results of 38 studies, and since then multiple meta-analyses have been carried out that ask slightly different questions, such as whether phonics improves the reading outcomes for struggling children, whether phonics has long-lasting effects, whether phonics works for children learning English as a second language. I went through all the meta-analyses and show that they provide little or no evidence that phonics improves the reading of text, reading comprehension, reading fluency, or spelling in any population of children, either in the short- or long-term. I also show that there is no evidence that reading outcomes have improved in England following over a decade of legally required phonics. It is not that the evidence shows that phonics is bad, it is that there is little or no evidence that phonics is better than common alternative methods. You can find out the details in the linked articles and blogposts below.

The primary reaction to my claim amongst researchers is profound skepticism, and not uncommonly, hostility. How could all the experts be wrong! One thing to note is that I am one of the experts. I’ve published over 100 peer reviewed journal articles, many on the topic of reading, and many in the most prestigious journals in psychology and education. So not all experts agree. More importantly, there are numerous examples of research communities in education, psychology, neuroscience, etc. strongly supporting demonstrably false or unsupported claims. I recommend watching the following talk entitled: “Publication bias and citation bias: A major reason why you can’t believe much of what you read” by Professor Dorothy Bishop, a world-leading developmental psychologist at Oxford University. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQGD_Uw-Bj8&t=2s). It is an eye-opening talk that highlights how politics and poor research practice can and do lead to false conclusions.

Bishop does not consider the case of phonics, but the factors that contribute to the false conclusions in other domains apply here as well. If you take her case seriously, you should not simply accept the conclusion that the science of reading supports phonics, but instead, ask whether my critique stands up to scrutiny. And you would think researchers would be highly motivated to respond to my points given that I have been challenging leading researchers by name and my critique of phonics was published in one of the most prestigious journals in educational psychology (currently ranked 2nd out of 339 journals according to Scimago Journal & Country Rank, see: https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=3204). But for the most part, my arguments are ignored, and researchers continue to make the claim that the science of reading strongly supports phonics. I’ve detailed multiple (sometimes amusing) examples of leading researchers failing to respond to straightforward points in my blogposts. To be fair, Jennifer Buckingham, a leading proponent of phonics in Australia, did respond to Bowers and Bowers (2021) who identified a long list of errors in her work, tweeting:

Of course, the strength of an argument does not hinge on being person making the argument. Still, if I was this layperson depicted in this cartoon, challenging all the top scientists without any relevant background, it would at least be understandable why researchers might fail to respond. Top scientists are busy, and there are too many cranks in this world to pay attention to them all. But it is just poor scientific practice for researchers to ignore critiques published in top journals. And as highlighted by Dorothy Bishop in the video above, ignoring published research that challenges to the status quo is not unique to the field of reading instruction.

What is the theoretical problem with phonics and whole language?

Apart from the lack of evidence that phonics is more effective than whole language (or the reverse), the theoretical motivations for both approaches are also seriously flawed. Let’s start with phonics. On this view, the English writing system follows the “alphabetic principle” which is a fancy way of saying that letters represent sounds. From this, it is argued that the goal of initial reading instruction should be to teach children these letter-sound correspondences so that they can sound out words. Sometimes this is called “cracking the orthographic code”. Who could object to teaching children the alphabetic principle? After all, English words are composed of letters, and skilled readers can name words aloud.

But there are some complications. One sign that something is wrong with this principle is that there are so many exception words in English (or “sight words”). That is, words that have surprising spellings given their pronunciations. The linguist David Crystal (2003) estimates that phonics can only explain about 50% of English spellings (in other more “regular” languages like Italian and Spanish it would be near 100%). Another obvious sign of a problem is that most homophones (words with the same pronunciation but with different meanings) are spelt differently (e.g., <to>, <two>, and <too>). If English followed the alphabetic principle, shouldn’t homophones be spelt the same way?

What should we make of these sight words and homophones? Should we just shrug our shoulders and conclude that this is one of those cases in which the (many) exceptions prove the rule, in this case, the alphabetic principle? Or conclude that the English writing system needs reform, and in the meantime, we just need to do the best we can with phonics? It is important to highlight that these conclusions constrain instruction. Question: Why is there a <g> in <sign>? Why is it <dogs> with an <s> rather than *<dogz> with a <z>? Why is <does> spelled as it is instead of *<duz>? Why is it <Christmas> not <Chrismas>? Answer: Because English spellings are crazy. How should children learn these exception words? Remember them by rote. There really is not much more to say if the English spelling system follows the alphabetic principle, however poorly.

But the alphabetic principle is wrong (or to be charitable, incomplete). Linguists have long known that the letters in words represent more than sounds. Rather, letters are used to represent the building blocks of words, both in term of sound (phonemes) and meaning (morphemes). As the famous linguist Venezky (1967) put it:

“The simple fact is that the present orthography is not merely a letter-to-sound system riddled with imperfections, but instead, a more complex and more regular relationship wherein phoneme and morpheme share leading roles”.

This undermines the main theoretical justification for a core claim of phonics, namely, instruction should first focus on the letter-to-sound correspondences and ignore the letter-to-meaning regularities.

What about the theoretical motivation of whole language? Whole language does not emphasize any of the spelling regularities in English (phonological or meaningful), and instead, was initially motivated by the claim that learning to read is as natural as learning to speak. And indeed, children don’t need to be explicitly taught their native language, they just need to be immersed in a rich linguistic environment. Humans have been speaking for all recorded history, and every community communicates with language – no anthropologist has ever found an isolated group of people in some remote part of the world that does not speak. Impressively, a community of children will invent their own language if they are not taught, even when deaf from birth (by inventing a new sign language). Proponents of whole language were inspired by these observations and made the further claim that children will learn to read as long as reading is done in a meaningful context. In practice, whole language does include some instruction in letter-sound correspondences, but these correspondences are not the focus of instruction. Rather, the focus is on presenting children with meaningful and engaging texts from the start, with instruction focused on communicating meaning rather than sounds.

Proponents of phonics are right to challenge the claim that learning to read and learning to speak are equally natural. The theory runs into the stark fact that most people did not read only a few hundred years ago, and still today you can find many communities that are largely illiterate. Clearly, reading and writing are not natural in the same sense of spoken language. There really is no basis for the claim that whole language exploits our natural capacity to learn a native language.

But proponents of whole language may be onto something with regards to their critique that phonics instruction is not sufficiently engaging. Here is a quote from two prominent reading researchers from Oxford who are strong supporters of phonics but who also note that the evidence for phonics is quite disappointing:

“We believe that one important next step for intervention studies is to take seriously issues to do with pupil motivation. For interventions to be truly effective, it is likely that they will need to increase students’ enjoyment of reading” (Snowling and Hulme, 2014).

And indeed, there is evidence that phonics has not helped in motivating children to read. For example, one of the main international tests of reading achievements is called Progress in International Reading Literacy Study or PIRLS. Not only is there no evidence that the legal requirement to include phonics in England since 2007 has led to better reading outcomes on this (or any other) reading assessment test, the data from the most recent PIRLS 2016 ranked English children’s enjoyment of reading at 34th, the lowest of any English-speaking country.

I’ve gone into some detail of my criticisms of phonics and whole language because they dominate current instruction. The current scientific consensus for phonics is so strong that most researchers do not take seriously any outsiders (like me) who question the evidence for phonics or consider alternative approaches (like SWI). Indeed, it is hard for researchers to even see the straightforward flaws in their arguments, and they don’t feel the need to respond to direct challenges. Confirmation bias is a powerful thing. We are now in this absurd situation that there are growing legal mandates to teach phonics when there is little or no empirical evidence that it is more effective than alternative methods and when the theoretical motivation for phonics is flawed.

What is the theoretical motivation of SWI?

As highlighted by Venezky (1967) in the quote above, spellings encode both phonology and meaning. Indeed, according to Chomsky and Halle (1968), the English writing system is near optimal in encoding both phonology and meaning. And this provides the main theoretical motivation of SWI, namely, reading instruction in English should be designed around both the phonological and meaningful spelling regularities of English. The premise that instruction should be designed around the writing system should not prove too controversial, and indeed, one of the main theoretical motivations of phonics is that children should be taught how the writing system works. It just turns out that phonics is based on a mischaracterization of the writing system where SWI is based on the correct linguistic description of the system.

Another key motivation of SWI is that instruction should be engaging and motivating for children, and nothing motivates more than understanding. SWI, unlike phonics, can address the most common question that children have: Why. Why is it <dogs> not <dogz>? Why is there a <g> in <sign>? Why is there a <t> in <Christmas>? A third and related motivation is that learning is best and most enjoyable when a child (or adult) can organize the to-be-learned information in a meaningful way. Indeed, the importance of studying information in a meaningful manner is uncontroversial given that the effects on memory and learning are so strong. Importantly, these three theoretical motivations for SWI are linked: It is only when a teacher understands the writing system that he or she can address “why” questions and design lessons in a way that highlight the meaningful organization of words.

So, how does the English writing system work?

The standard view is that letters represent sounds, and indeed, that is one job of letters. But letters are also used to represent meaning, through morphology (and through etymology, not considered here). The later job is less familiar, but it is important, and indeed, when word pronunciation and morphology collide (as explained below), the spellings follow the meaning. Furthermore, letter-sound correspondences are organized within morphemes. So even if you only care about the letter-sound correspondences, or more technically, grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs), you should not ignore morphology (as done in phonics).

Here is a quick lesson in the critical role of morphology in the English spelling system. Some of this is relevant to reading instruction from the start, and some of this is relevant for instruction in slightly older children. A morpheme is a basic unit of meaning in a spoken or written language, and morphemes come in two forms, namely, bases and affixes. A base encodes the main kernel of meaning of a word and an affix modifies the meaning of the base. For instance, the word <dogs> contains the base <dog> and the affix <s>. The <s> modifies the meaning of the <dog> by indicating there is more than one dog. And a critical feature of English is that the spellings of bases and affixes remain consistent even when the pronunciation of the base or affix differ across members of the morphological family. For example, the words <sign>, <resign>, <design>, <signature>, <designate> and <designation> are part of the same morphological family (they all share the base <sign>), and the spelling of base remains constant despite its different pronunciations in some words (e.g., <design> vs. <designate>).

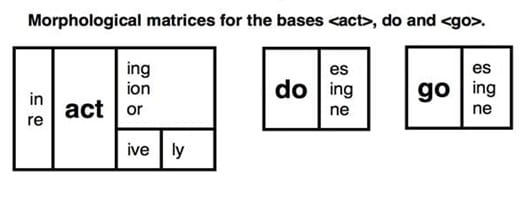

Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is the morphological matrix that provides a compact visual depiction of morphological families. For example, consider the morphological families formed from the bases <act>, <do> and <go> in Figure 1. Once again, and contrary to the alphabetic principle, the spellings of the base remain consistent across all members of the morphological families even when changes in pronunciation occur (e.g., “acting” vs. “action”; “do:” vs. “does”; “go” vs. “gone”). These are all examples of pronunciation and morphology colliding, with the spellings following the meaning. The same applies to affixes. For example, consider the suffix <ed> that is consistently spelled in jumped, played, and painted even though it is pronounced differently each time (/t/, /d/ and /əd/, respectively). These examples are not cherry-picked; they are the norm. Rather than respecting an alphabetic principle, the English spelling system is better described as respecting a morphological principle that prioritizes the consistent spellings of morphemes over phonemes. Once you understand the logic of the system, it makes no sense to consider the word <doing> regular and <does> irregular, as <done> in phonics.

The morphemes in a morphological matrix not only have consistent spellings, the words you can build from a matrix also share a common meaning due to their shared base. In many cases the meaning of morphologically related words is transparent (e.g., <help>, <helpful> and <helpless>), while in some cases the meaning relation is less clear, but most often, it can still be appreciated when pointed out (e.g., the word <disease> contains the base <ease>; disease is the state of not being at ease; the word <question> contains the base <quest>; a question is a search for knowledge). And in all cases, the words in a morphological matrix have a common historical meaning (etymology), but that is for another time.

How do GPCs fit into the matrix? One relevant point has already been noted, namely, the matrix highlights how spellings tend to follow morphology rather than phonology when there is a clash, and therefore, it is necessary to have flexible GPCs. It explains why the <o> grapheme maps onto different phonemes in <do> and <does>, or why the <t> grapheme maps onto different phoneme in <actor> and <action>. Put another way, the flexible grapheme-phoneme correspondences are a feature of the system not a bug. The alphabetic principle has no explanation for why <action> is not spelt *<acshion>, so phonics calls it an exception word.

In addition, morphology constrains GPCs because GPCs only occur *within* morphemes. Consider the word <react>. If you ignore morphology, it is not possible to know whether the letter sequence <ea> corresponds to a single grapheme <ea> that maps to a single phoneme (so that the word is pronounced “reeked”), or corresponds to two graphemes, <e> and <a>, that map onto to two phonemes (so that the word is pronounced correctly). But as soon as you appreciate that that the <ea> sequence straddles a morpheme boundary, <re + act>, then you know that the letter sequence <ea> corresponds to two graphemes. That is, the meaningful parts of the word constrain the letter-sound correspondences. Phonics provides no explanation for this because phonics ignores the role of morphology in GPCs. Again, this is commonplace (given that most words are morphologically complex).

Of course, there is much more to say on the topic, and I go into some more detail in the blogposts and articles listed below. But I hope you can see how letters are not all about sounds, that words can be organized into morphological families that share spellings and meanings, and that grapheme-phoneme correspondences are organized within morphemes. Once you understand the logic of the English writing system, you understand why we don’t spell <action>, <does>, and <Christmas> as <acshion>, <duz>, and <chrismas>, respectfully. To call these words “exception” (as done in phonics) is to misunderstand the system. And more importantly, understanding the system makes it possible to design forms of instruction that are more engaging and that exploit the fact that we all learn best when information is studied in a meaningful and organized manner, as described next.

Teaching with SWI

Jeff in the story was being introduced to SWI. Jeff has struggled with phonics (sometimes children like this are described as “treatment resistors” – treatment resistors!) and he is being told for the first time that his writing system makes sense, that there is another way to learn that does not involve more of what he finds so difficult, namely, sounding out words as prescribed by phonics. Of course, many children learn just fine with phonics, just as many children learn just fine with whole language. But far too many children continue to struggle in school systems that emphasize whole language or phonics (and to similar extents as demonstrated on various international tests of reading).

A SWI lesson might begin with a conversation about the meanings of a set of morphologically related words, such as <do>, <does>, and <done> (“I do my work”, “she does her work”, “we are done”). The words can then be written down using simple graphical methods (e.g., morphological matrices) to highlight the consistent spelling-meaning connections in morphological families (the <do> in <does> and <done>). In this context, children can learn the mapping between <d> → /d/, that the <o> grapheme can write more than one phoneme, and that the <s> grapheme in <does> spells the /z/ phoneme. All GPCs can be taught explicitly in this way using morphological matrices for a wide set of interesting word families, so that children learn GPCs, word spellings, and vocabulary at the same time.

To be more concrete, have a look at this video that depicts an SWI lesson in preschool: https://goo.gl/izAcXP. This lesson investigates the morphological family of <rain> using a “word web” rather than a morphological matrix (perhaps more appropriate for the youngest children). Again, the first thing to note in the video is that SWI is teaching children a wide range of skills together: spelling, vocabulary, and how to pronounce words. And notice, because the focus on meaning, it is easy to organize fun and meaningful games. Some of the children in the video already know how to read these words aloud, others do not (and there is always a big range in skills in young children), but all can engage in the games while they learn about their writing system. Here is another very short video but using a morphological matrix. Check out the bowtie! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yeIri8ymPro

It is important to emphasize how different SWI is to phonics and whole language. SWI starts by telling children that their writing system makes sense, and children can be “word detectives” using tools like the morphological matrix to make sense of the meanings of words, learn why words are spelt the way they are, and learn (the flexible) GPCs, all at the same time. Learning vocabulary, spelling, and GPCs together is central to SWI, because words only make sense this way. Interestingly, there is growing evidence that vocabulary, spelling, and morphological knowledge are all useful for learning GPCs. So even if you take the view that learning GPCs is the key for “cracking the orthographic code”, it makes sense to learn these correspondences in the context of spelling and vocabulary instruction. SWI teaches simple concepts at the start and more advanced aspects of the writing system can be taught in later years. That is, SWI is a form of instruction that is relevant for all ages of children (and adults).

By contrast, phonics teaches GPCs in isolation (<s> is pronounced /s/, <t> is pronounced /t/), with a specific ordering of the GPCs prescribed (e.g., teach the most frequent graphemes first). Following this, it is often argued that children should practice these correspondences in “decodable books” – that is, books composed of regular words. Books with sentences like: “Zac is a cat. Zac sat on a can”. But it is not just poor books that often follow-on from phonics. Teachers in England are teaching children how to pronounce nonsense words (e.g. “blap”) in order pass the Phonics Screening Check (a legally required test in England that assesses how effectively children have learnt their GPCs – if they do not pass a criterion more phonics is prescribed). And some proponents of phonics are now selling expensive tests that assess the naming of nonwords so that teachers can predict performance on the Phonics Screening Check. Madness.

Proponents of phonics do emphasize that phonics is not enough, and that children also need vocabulary and spelling instruction, as well as other forms of instruction. But the focus is first on teaching GPCs in isolation of morphology, and there is no consideration of how spelling, meaning, and phonology work together to make sense of words. There are no word detectives, no word investigations, no figuring out how the system works. Instead, children need to work away at learning isolated GPCs and perhaps reading decodable books, a process that is especially frustrating for children who have poor phonological skills (the main cause of dyslexia). The general view is that children can start to enjoy the meaning of written words after they learn GPCs, not realizing that children could have learned these correspondences in a meaningful, more engaging, and perhaps more effective manner. And according to proponents of phonics, if all goes well, phonics can be dropped in Grade 2 or 3, with more phonics prescribed for the treatment resistors.

And although researchers who advocate phonics repeatedly highlight how phonics is not enough, I am not aware of any of these researchers citing the morphological matrix or other tools of SWI that can be used for instruction after phonics. It is quite extraordinary that the simplest way of depicting morphological families, namely, the morphological matrix, is almost completely neglected in instruction. Indeed, the selective emphasis on teaching GPCs is so extreme in phonics that there is little research into how to best teach morphology, and most teachers have little knowledge of morphology. Of course, it is not only proponents of phonics who ignore morphology. Proponents of whole language also give little or no consideration to morphology given that this approach gives little emphasis to either the letter-sound or letter-meaning regularities in words.

It is long past time that researchers face the fact that the evidence for phonics is poor and start considering alternative approaches. I would argue that SWI is the most promising alternative, not only because it teaches children the logic of their writing system, but because there is already some research suggesting that SWI is effective (see papers below). It is important to acknowledge that the empirical evidence for SWI is only preliminary at this stage given the limited research that has been carried out to date, and there are some obvious challenges in training teachers in delivering SWI. But now is the time for grant agencies to divert more funding to SWI and other approaches that emphasize the important role that morphology plays in our writing system. Unfortunately, given the politics of the field, obtaining funding for anything challenging phonics is very hard to come by. Any rich benefactors please get in touch!

Reading instruction should be fun!

And remember, a key point of SWI is studying the logic of words can make instruction fun. From simple lessons where children learn GPCs within simple morphological families, to learning the meaning relation between SCIENCE and CONSCIENCE. Watch the video of kindergarten studying the RAIN family and ask yourself whether this might be more fun than learning the /r/ grapheme, followed by the /a/ grapheme, etc. And here are some word investigations taken from real classrooms from kindergarten to Grade 3, much like the lessons depicted in our story with Jeff.

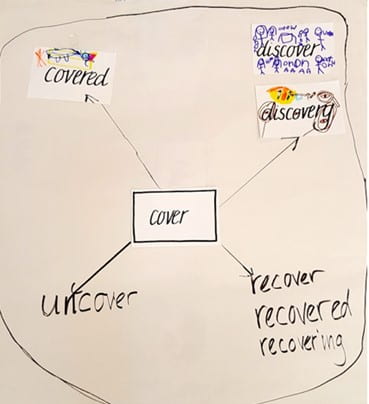

This is a “word web” created around the base <cover> in a kindergarten class. Children were given cards with words written on them, and then they went around the room to find others with words with the <cover> base. Even children who could not read could get involved by looking to see if their words all had the right letters. Note, young children know the meaning of many of these words when spoken, but it is unlikely they had noticed a meaning connection between “cover” on the one hand and “discover” and “discovery” on the other. This activity allows the teacher to discuss the idea that if something is ‘covered up’ and then you ‘uncover it’ then you have made a ‘discovery’!

This is a picture of a Grade 1 student and her mother showing off a matrix they made together at home. Notice the denotation ‘heart’ written in the banner of the matrix. If you look up the history of the word “courage” it goes back to a Latin root cor for ‘heart’. This investigation lets us talk about the idea that someone who is ‘courageous’ has ‘heart’.

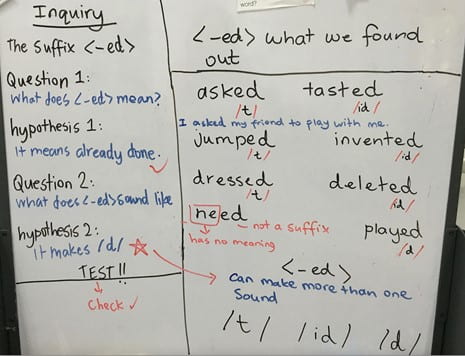

Investigating the <ed> suffix in a Grade 2/3 class. The lesson explores the meaning of the <ed> suffix, explores whether the letter string <ed> in the word <need> constitutes an <ed> suffix, and highlights the different ways the <ed> suffix is pronounced.

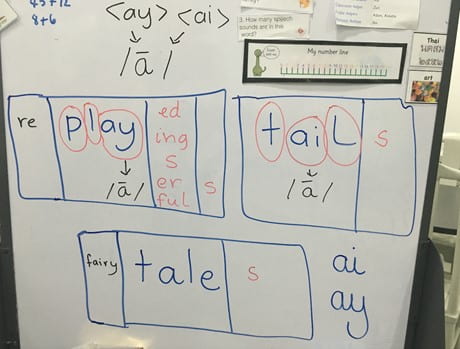

Learning grapheme-phoneme correspondences in the context of morphological families in a Grade 2/3 class. In this lesson children learn that different graphemes <ay> and <ai> map onto the same phoneme and are being exposed to the “homophone principle”, namely, most homophones (in this case <tail> and <tale>) are spelt differently. The fact that most homophones are spelt differently reflects the fact that spellings are not all about sound but also about meaning.

Final note about science

I have highlighted how the science of reading does not support phonics the widespread claim that phonics instruction is more effective than other forms of instruction like whole language. And I’ve pointed you to a video by Dorothy Bishop who highlights how many findings in science are false. But I don’t want to leave you with the view that the results of science can be safely ignored. Science is the best method we have for addressing fundamental questions of nature as well as the many critical societal challenges we face (e.g., global warming). The problem is with bad science, or unjustified conclusions drawn from good science. And the tell-tale sign of this is an unwillingness of the powers-that-be to engage with the arguments of critics. Especially when the criticisms are published in the top journals in the field. You can bet that a paper challenging global warming published in a top journal would attract lots of responses by researchers in the field. Because they would have something to say.